Existentialism, as Sarah Bakewell says, “is more of a mood than a philosophy” and describes anyone “who has ever felt disgruntled, rebellious, or alienated about anything.” And by that parameter, literature and philosophy is full of existential writing throughout history. However, for obvious reasons, Sarah Bakewell follows the more concrete history of modern existentialism to create this wonderful book on the lives and writings of modern existentialist philosophers from Husserl and Heidegger to Sartre and Beauvoir to Colin Wilson.

Often, philosophy can be pretty tough to read for us mere mortals and seems to be rife with the heavy stuff that would either require too much of a mental exercise or put us to sleep. I don’t know about you, but the usual perception of philosophy around me has been that it is dry. Not fun. If you call yourself a philosopher, you’d instantly be judged as someone super serious, without a shred of humor, and possibly jobless too. At the Existentialist Cafe by Sarah Bakewell turns these stereotypes on their heads by showing you a world of philosophers that is so full of life that it makes you want to be right there with these people as they make history. It makes me want to be friends with them.

The birth of modern existentialism [was] down to a moment near the turn of 1932-3, when three young philosophers were sitting in the Bec-de-Gaz bar on the rue du Montparnasse in Paris, catching up on gossip and drinking the house speciality, apricot cocktails.

Sarah Bakewell

True philosophy needs communion to come into existence. Uncommunicativeness in a philosopher is virtually a criterion of the untruth of his thinking.

Karl Jaspers

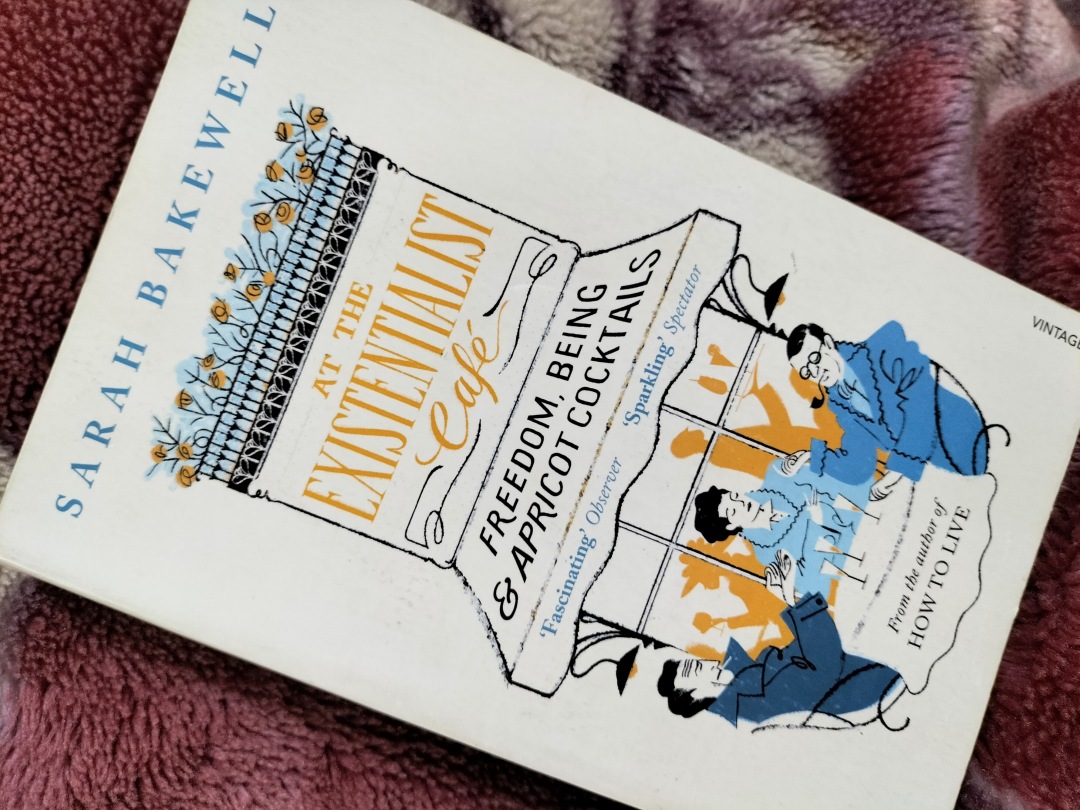

The first thing that draws you in is the beautiful cover, which shows an animated Albert Camus (history says that it should be Raymond Aron, but look at the guy! It’s Camus for sure), Simone de Beauvoir, and Jean Paul Sartre sitting in a cafe, chilling with cocktails. What’s not to like? Still, I picked this book with a tiny bit of wariness, expecting it to be challenging. However, I was pleasantly surprised to see how welcoming this book is in its simple language and relatable humor. Sarah Bakewell starts with the basics and goes into the main features of existentialist philosophy, explaining how this philosophy emerged from phenomenology, which was about describing things as they are, focusing on lived experience rather than abstract concepts like beauty and divinity. She goes on to explain how this focus on lived experience led to a preoccupation with our existence and the connected ideas of freedom and purpose.

Besides claiming to change how we think about reality, phenomenologists promised to change how we think about ourselves. They believed that we should not try to find out what the human mind is, as if it were some kind of substance. Instead, we should consider what it does, how it grasps its experiences.

Sarah Bakewell

However, even at the beginning, this book never feels like an informative textbook or companion text on philosophy (not that there is anything wrong with those :P). Bakewell very beautifully explains everything by weaving these details into the life stories of these philosophers. Thus, this might be a non-fiction book on philosophy, but the philosophers have been treated as lovingly as characters of a novel. In fact, this is my favorite part of this book. In school, we used to learn these things as abstract concepts that almost seemed to come from a knowledge bank rather than real people. For me, Sarah Bakewell humanizes philosophy by tracing the roots of these ideas in the experiences of the people who wrote them and in the kind of world that they lived in.

Modern existentialism emerged between two of the biggest global crises in recent history: the two world wars, and in countries that were at the center of the action: Germany and France. Knowing what happened, it’s no wonder that existential philosophy took the direction it did, why it grappled with things like what makes our lives meaningful, and what happens when this meaning breaks down. Of course, no two existentialists had the same opinions. In fact they diverged and disagreed so much that many of them didn’t even agree to being called existentialists. Sartre was inspired by Heidegger’s writing, which helped him flesh out the beginnings of existentialist philosophy. However, at a later point, Sartre and Heidegger were so annoyed with and put off by each other that they refused to meet after repeated attempts by a mutual friend to make it happen. Sartre and Beauvoir were good friends with Camus, but ended up getting estranged after their political views took them in the opposite directions.

So, existentialist philosophy is not simply about the ideas and perspectives of these philosophers, but also about how they lived these ideas. Each had a unique way of not just writing philosophy based on their lived experience but also of living their life based on their philosophy. And seeing that interplay is what makes this book so interesting. On that note, I loved reading about Sartre and Beauvoir’s unique relationship. It was both endearing and enduring, with each one encouraging the other to be better versions of themselves, while respecting their individuality.

Sartre was always the first to read Beauvoir’s work., the person whose criticism she trusted and who pushed her to write more. If he caught her being lazy, he would berate her: ‘But Castor, why have you stopped thinking, why aren’t you working? I thought you wanted to write? You don’t want to become a housewife, do you?’

Sarah Bakewell

The book made me further like the philosophers I already knew of, such as Sartre, Camus, Beauvoir, and Arendt, and curious about those I hadn’t encountered earlier, such as Mearleau-Ponty and Kierkegaard. I’d highly recommend it to anyone who’s interested in philosophy, and especially if you’re new to existentialist philosophy.

Reblogged this on When the nib trips… and commented:

This is a long-due review of one of my favorite reads last year, At the Existentialist Cafe: Freedom, Being, and Apricot Cocktails by Sarah Bakewell.

LikeLike